Most people are aware of Lyme disease and are on guard for ticks when they’re in certain outdoor environments such as wooded and grassy areas.

We now know that Lyme-like symptoms are common in patients with Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever (TBRF), caused by TBRF Borrelia group. TBRF Borrelia can also be transmitted by a lesser-known family of ticks that behaves very differently than most others, often setting up residence indoors and feeding on unsuspecting hosts while they sleep.

The following article provides some basic information about TBRF and where you are most likely to be at risk for exposure to the ticks that transmit it. You’ll also learn how you can recognize potential signs of TBRF and some of the best ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat it.

TBRF is a Bacterial Infection Transmitted by Select Species of Ticks

TBRF is an infectious disease that is caused by Borrelia bacteria, a group of spiral-shaped bacteria that is transmitted to humans and other mammals through the bite of certain species of ticks. Although TBRF Borrelia is closely related to Borrelia burgdorferi, it does not cause Lyme disease.

TBRF can be transmitted by certain species of both soft and hard ticks, but the soft tick-borne variety is better known and more prevalent. That said, it is important to know the basic facts about each:

Soft Tick-borne Relapsing Fever

First discovered in the early 1900s, Soft Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever can be caused by various strains of the relapsing fever Borrelia bacteria, including B. crocidurae, B. duttoni, B. persica, B. latyshervi, and B. hispanica, B. venezuelensis, B. mazotti, B. hermsii, B. turicatae, and B. parkeri. The three known to cause TBRF within the United States are Borrelia hermsii (B. hermsii), B. parkerii and B. turicatae, with the most common being B. hermsii.

Each strain of bacteria is associated with a specific species of soft ticks, which are all part of the genus Ornithodoros. The ticks acquire the Borrelia bacteria by feeding on already-infected rodents. The bacteria can then be transferred to humans and other mammals through their saliva as they bite through the skin to feed. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), infected ticks can transmit TBRF within 30 seconds of initiating feeding.((https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6403a3.htm))

Image Source: https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=5970

SOFT TICK (ORNITHODOROS)

Unlike hard ticks, which are distinguished by their hard, outer shield or back plate, soft ticks have more-rounded bodies and lack a tough exterior shell. Also unlike hard ticks, soft ticks tend to spend daylight hours tucked away in rodent burrows inside buildings or in natural settings such as caves.

Emerging to feed primarily at night, they will attach to people, pets, or other mammals as they sleep, feeding very quickly (usually dropping off of a host within an hour). This differs from hard ticks, which can attach to a host and feed for up to two days. Adult soft ticks can also live for many years, whereas adult hard ticks typically die shortly after reproducing.

Hard Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever

Hard Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever infections in humans are caused by Borrelia miyamotoi—a specific strain of Borrelia bacteria discovered in Japan, in 2005. The first human case of B. miyamotoi infection was reported in Russia in 2011. The first case in the United States was reported in 2013.

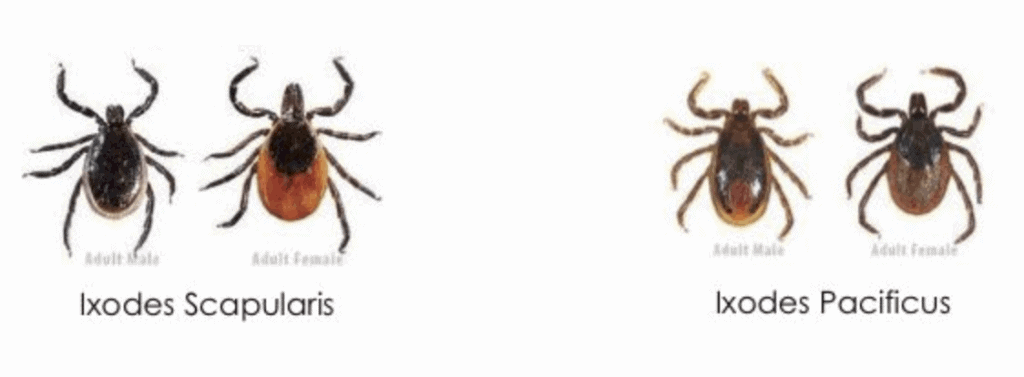

Currently, only two types of deer ticks, which are part of the hard-tick family, are known to transmit the B. miyamotoi bacterium. Within the United States, these are the Eastern blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) and the Western blacklegged tick (I. pacificus).

Where Most TBRF-Infected Ticks Live—and Hunt

B. hermsii, the most common TBRF-causing bacteria within the United States, is transmitted by the soft tick, Ornithodoros hermsi(O. hermsi.). These ticks are found in mountainous regions within the United States, typically at altitudes between 1,500 and 8,000 feet. They live within rodent burrows, including those of mice, squirrels and chipmunks. People most often encounter these ticks in rustic, rodent-infested cabins that are located at higher-altitude, coniferous forests. At night, these ticks will venture out from their host burrows to feed on other prey, including humans, as they sleep. Because their bites are typically painless, most people don’t even know they’ve been bitten when they wake up.

Other species of soft ticks that transmit less common strains of TBRF-Borrelia are the O. parkeri ticks and the O. turicata ticks. These ticks are primarily found at lower elevations in the caves and burrows of ground squirrels, prairie dogs, and even burrowing owls.

Photo taken by Gary Hettrick RML, NIAID. Image Source: https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/transmission/index.html

At night, these ticks will venture out from their host burrows to feed on other prey, including humans, as they sleep. Because their bites are typically painless, most people don’t even know they’ve been bitten when they wake up.

By contrast, the two types of deer ticks that transmit the hard-tick-borne relapsing fever infection are primarily found outdoors. The Eastern blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) is typically found in wooded and grassy areas where the animals they feed on live and roam, particularly their reproductive host—the white-tailed deer. The Western blacklegged tick (I. pacificus) is located along the Pacific Coast, particularly in Northern California. However, they have also been found inland to eastern Oregon, western Utah, and Arizona.

Recurring Fever Can Be a Telltale Sign of TBRF—But Not Always

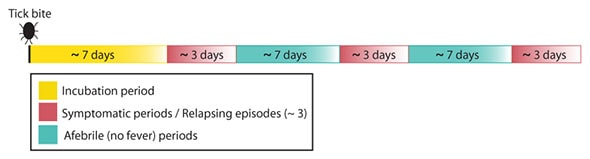

One of the most recognizable symptoms of TBRF can be the onset of a high fever that lasts three to five days, followed by a brief recovery of approximately seven days, followed by another three days of fever.

Image Source: https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/symptoms/index.html

However, recent studies reveal that many patients with TBRF don’t recall having relapsing fevers but do report symptoms that are similar to those for Lyme disease, including fever, headache, fatigue, chills, myalgia, joint and muscle pain, loss of appetite, nausea, disorientation or memory loss, lack of coordination, as well as more severe neurological conditions.

If you suspect TBRF, consult your healthcare provider immediately. Diagnosis of TBRF is usually confirmed by laboratory tests.

Areas and Seasons With the Highest Reported Cases

TBRF exists((https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/tickbornediseases.pdf)) around the world; but within the United States, it was thought to occur most commonly in 14 states—Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. However, with the recent addition of Hard-Tick-Borne Relapsing Fever caused by B. miyamotoi, TBRF is also prevalent in areas endemic for Lyme Disease.

Image Source: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6403a3.htm

Infected ticks can be active and transmit TBRF to people and pets at any time of the year; however, most reported cases occur in the summer when people are vacationing in mountain cabins that harbor mice and other rodent nests, where soft ticks thrive.

Prevention Includes Being Selective About Where You Sleep

One of the best ways to limit your risk for TBRF is to avoid sleeping in rodent-infested buildings whenever possible. Keep in mind that even if you don’t see rodent nests, other signs such as droppings can be a good indicator that a building is infested. Be sure to notify owners of vacation or rental properties of these signs if you find them. And if you own the property, consult with pest-control specialists to identify and address potential infestations and create an ongoing pest-control plan to mitigate future risk.

Also steer clear of other natural sites that may be infested with rodents, including animal burrows and caves. If you are in areas where tick populations are suspected, using repellent that contains DEET may help reduce your risk of tick contact.

TBRF Can Be Treated With Antibiotics

If you or a loved one is diagnosed with TBRF, your doctor will likely prescribe a seven- or 10-day course of antibiotics to treat. In a little more than half of all TBRF cases, patients develop a reaction to the drugs, called Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction.((https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3725823/)) According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, this reaction results in an acute exacerbation of a patient’s symptoms following the initial treatment of TBRF with an effective antibiotic. It typically begins within one to four hours of the first dose of antibiotics, and symptoms may include hypotension (low blood pressure), tachycardia (rapid heart rate), chills, rigor (tremors), and/or fever.

Treatment can take longer if a patient has a co-infection such as Lyme disease, Babesiosis or Bartonellosis. Mortality rates are very low for TBRF. However, it can lead to complications if women are infected while pregnant.

As with any tick-borne disease, if you suspect that you or a loved one has TBRF, contact your healthcare provider as soon as possible. Be sure to inform your doctor of any potential exposure you may have had to ticks and any specific symptoms you’ve noticed.

IGeneX offers a number of testing solutions to help physicians identify Borrelia, including PCR tests. You can also click here to order a tick-borne disease test kit directly from IGeneX.

Additional Resources

- https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/transmission/index.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/resources/15_260166_FS_APerea.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/relapsing-fever/clinicians/index.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3725823/

- https://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/1115/p2039.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6403a3.htm

- https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/tickbornediseases.pdf

- https://igenex.com/tick-talk/borreliosis-relapsing-fever-disease/

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/227272-overview#a6