What is Babesiosis?

Babesiosis, as with Lyme disease, is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected tick. However, in a similar fashion to malaria, Babesiosis is caused by microscopic parasites (intraerythrocytic) from the genus Babesia – also known as “piroplasms” – that infect red blood cells.

A Brief History of Babesiosis Disease

In 1888, Romanian pathologist Victor Babes identified the Babesia protozoan in the red blood cells of cattle. A few years later, in 1893, it was discovered that Texas cattle fever was caused by the transmission of Babesia through tick bites to cattle. Babesiosis is primarily known to occur in cattle and other domesticated animals, with Babesia bigemina causing Cattle tick fever in cattle, buffalo and zebu. The first case of human infection with Babesia was to a Yugoslavian cattle farmer in 1957, and the first case reported in the US was in 1966.

Since then, over one hundred different species of Babesia have been identified, although only a handful have been discovered to cause infection in humans. These species include Babesia microti, B. divergens, B. duncani (formally WA-1), B. MO-1, and B. bovis.

Babesia

How is Babesiosis Disease transmitted?

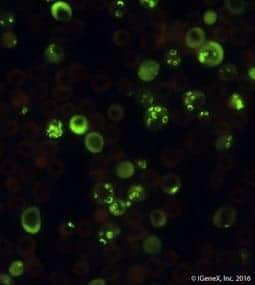

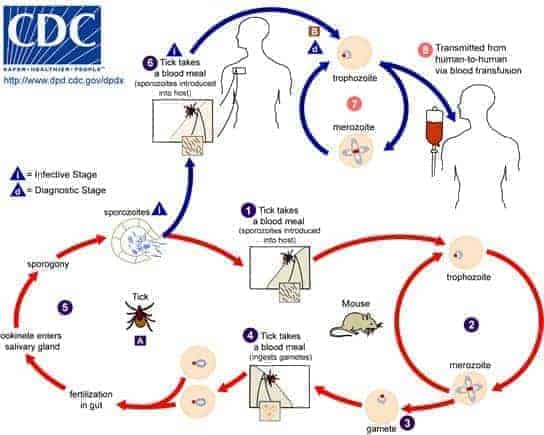

Not only is Babesia similar to the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in morphology, but it also infects red blood cells in the same way as P. falciparum. The definitive host of Babesia is the same hard-bodied ixodid tick that transmits B. burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease. The ticks are infected by feeding on infected larger mammals, such as cattle and roe deer, and rodents, with the white-footed mouse, Peromuscus Leucopus being the primary reservoir for B. microti. Humans are dead-end hosts.

Babesia is most commonly spread to humans during the tick’s nymphal stage, through its saliva when it bites into the skin. However, the parasite can be transmitted by ticks at various stages of their development. Nymphs are mostly found during warm months (spring and summer) in areas with woods, brush, or grass. Infected people might not recall a tick bite because the nymphs are very small (about the size of a poppy seed).

In the US, Babesiosis disease is spread by various ticks. B. microti is spread by the black-legged tick: Ixodes scapularis, the Eastern black-legged deer tick, found on the East Coast and in several mid-western states, and the Western black legged tick, Ixodes pacificus, found on the West Coast. [See Babesia micoti life cycle below]. B. duncani is transmitted by D. albipictus, the winter tick. In Europe, B. divergens is transmitted to humans through the sheep tick, Ixodes ricinus, also known as the castor bean tick. I. ricinus is not only a vector of Babesia, but also a reservoir host due to its transovarial and transstadial transmission of the parasite.

Other than the transmission of Babesia via ticks, the parasite can infect humans through blood transfusions from infected blood donors. Blood donors are not required to be screened for Babesia in the United States. Furthermore, Babesia has been reported to have been transmitted from infected mothers to their babies during pregnancy or delivery.

What are some common Babesia symptoms?

Babesiosis infection is expressed on a wide spectrum of disease severity that is usually dependent on the species of Babesia the patient is infected with, the immune status and age of the patient, or asplenia. Therefore, patients infected with the parasite usually display one of three symptom categories: mild to moderate flu-like symptoms, asymptomatic infection, or severe infection.

Most patients with Babesia will experience flu-like symptoms, beginning with high fevers and chills. As the infection progresses, patients may experience one or more of the following Babesia symptoms:

- Fatigue

- Malaise

- Muscle pain

- Headaches

- Myalgia

- Nausea

- Shortness of breath (“air hunger”)

- Vomiting

- Reduced appetite

- Depression

Flu-like Babesia symptoms usually begin 1-9 weeks after inoculation and are non-specific. In most patients (immunocompetent), the symptoms last for a few weeks to several months, but the infection will fully resolve. Co-infection with other infectious agents such as Lyme disease or Anaplasmosis may complicate and increase the severity of the disease.

A significantly small group of patients are asymptomatic. Asymptomatic parasitemia may continue for months to years. There are uncertainties over whether these patients are at risk for any complications. However, it is known that these carriers have the potential to transmit Babesiosis when donating blood, as no tests have been licensed yet for donor screening.

Severe cases of Babesiosis disease generally occur in immunocompromised patients and those with weakened immune systems, including patients with HIV, cancer, lymphoma, and serious health conditions such as liver or kidney disease. Additionally, Babesiosis can be life-threatening to patients with no spleen (asplenia), and the elderly. Some Babesia symptoms in patients with immunosuppressive conditions include severe hemolytic anemia (a breakdown of red blood cells), very low blood pressure, liver complications, and kidney failure.

How is Babesiosis geographically distributed?

Canine Babesiosis is common and known to have a global distribution. However, many people are unaware that human Babesiosis also has a worldwide distribution.

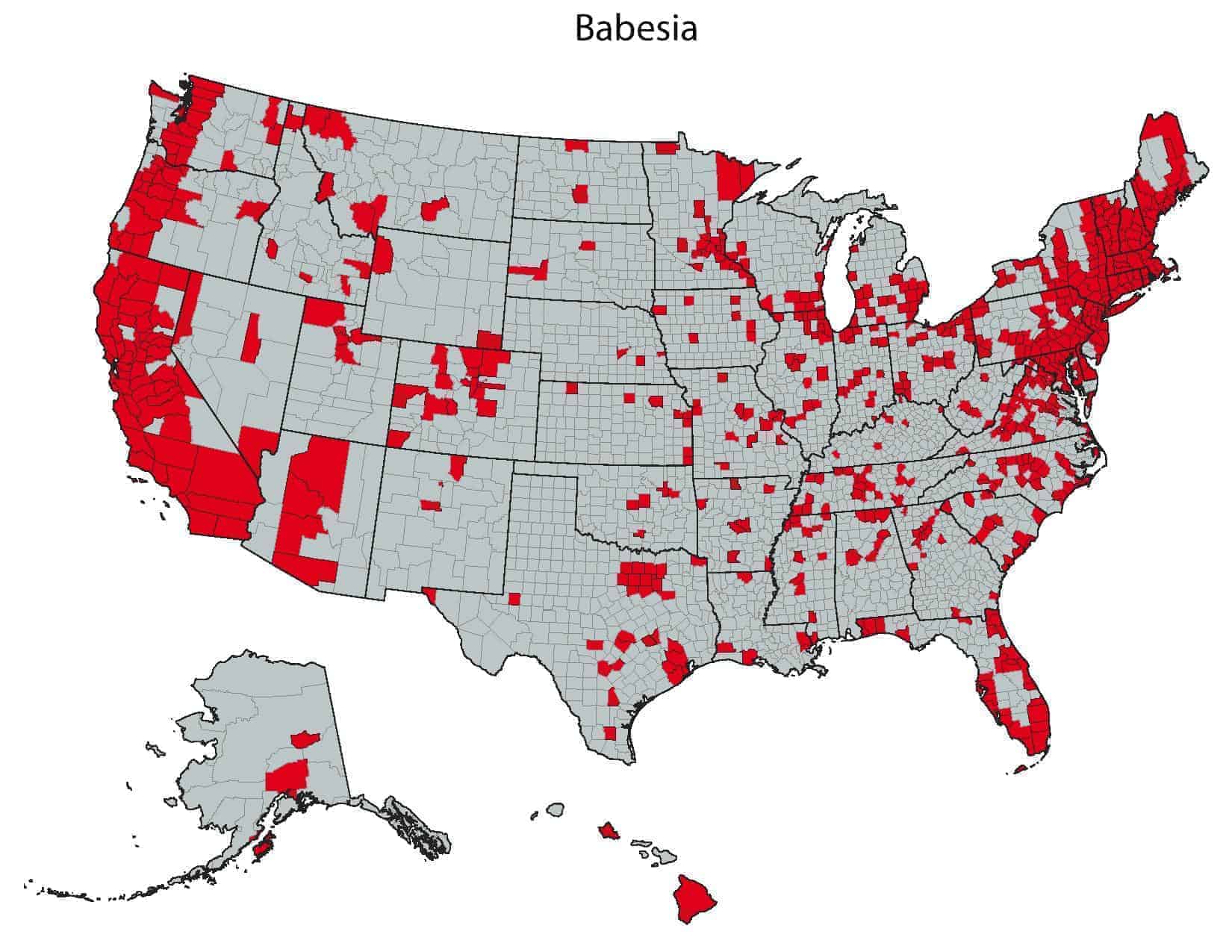

Babesia is endemic in the same regions as Lyme disease, since the intermediate host is the same tick that transmits B. burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease. We are seeing an increasingly mobile population, and as such, the spread of diseases outside their endemic areas has gone up. Babesiosis is no exception to this.

The most widespread cause of Babesiosis in humans in the United States is the Babesia microti species. B. microti was thought to be present only in the Northeast and Midwest parts of the US, but recently cases have been reported from Western Coastal regions of the US and Switzerland. Babesia duncani, also found in the United States, is on the rise and is emerging in states previously believed not to be harboring the species, such as parts of the Midwest and East coast, but primarily identified on the West Coast. B. duncani was formally called WA-1, as the species was only found in Washington state, but it was later renamed after being discovered in other Western states such as California and Oregon. The other species of Babesia found in the United States is B. MOI (B.divergens-like). B. MO1 (B. divergens-like) organisms have been identified in three cases, two from the Midwest (Missouri and Kentucky) and one from Washington State.

In Europe, most reported cases are due to B. divergens and occur in splenectomized patients. Isolated cases due to B. microti-like parasites have been reported over a wide geographic range in Europe, Australia, Asia, Africa, and South America.

How is Babesiosis Disease diagnosed?

More cases of Babesiosis go undiagnosed each year than those that are diagnosed, which stands at around one thousand cases annually. Furthermore, scientists believe at least 30% of patients infected with Lyme disease are infected with Babesia concurrently. The diagnosis of Babesiosis should be considered in patients who live or travel to areas that are endemic for Babesiosis and Lyme disease, and experience a viral-like illness or have been bitten by Ixodes ticks or recently had a blood transfusion. It is important to note that Babesiosis can present very similarly to malaria, which can sometimes lead to misdiagnosis in areas where malaria is prevalent, such as in parts of Africa.

Together, the risk of misdiagnosis and the non-specific nature of symptoms make Babesiosis a difficult disease to diagnose. Therefore, laboratory testing is required for diagnosis. IFA (Indirect Immunofluorescent Assay) tests are available for Babesia microti and Babesia duncani. However, to get a more comprehensive diagnosis – especially for seronegative patients – PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) tests and FISH (Fluorescent In-Situ Hybridization) tests are also available.

When testing for Babesia, testing for other tick-borne illnesses should also be considered. Patients should be examined by their healthcare professional, who will use clinical symptoms along with laboratory tests to find out whether a patient has Babesiosis or perhaps some other tick-borne infection.