There is a lot of talk about Lyme disease, as there should be – but Lyme isn’t the only tick-borne disease the public should be aware of. Recent advancements in research and testing technology have expanded our understanding of other tick-borne diseases. One such disease is Babesiosis, a malaria-like infection common in North America, Europe, and other regions that can be fatal for immunocompromised patients. We explore the Babesia & Lyme tickborne relationship.

What You Should Know About Babesia

Babesia is most commonly spread by ticks.

Like Lyme disease, Babesiosis infection is a vector-borne zoonotic illness, meaning it is transmitted from animals (typically small mammals in this case) to humans via a “vector”. The most common vector spreading Babesiosis disease is the tick. Like other tick-borne diseases, Babesia most often infects humans via ticks in the nymph stage – young ticks that can be as small as poppy seeds, making it very hard to detect and remove them in time to prevent disease transmission. However, ticks at any stage of development can transmit Babesiosis.

Though Babesia ticks are the most common way Babesia spreads, the parasite has been known to infect humans through blood transfusions (blood donors are not screened for Babesia in the United States). The CDC also cites evidence supporting transmission from infected mothers to their infants during pregnancy or delivery.

Babesia is widespread in North America, Europe, and beyond.

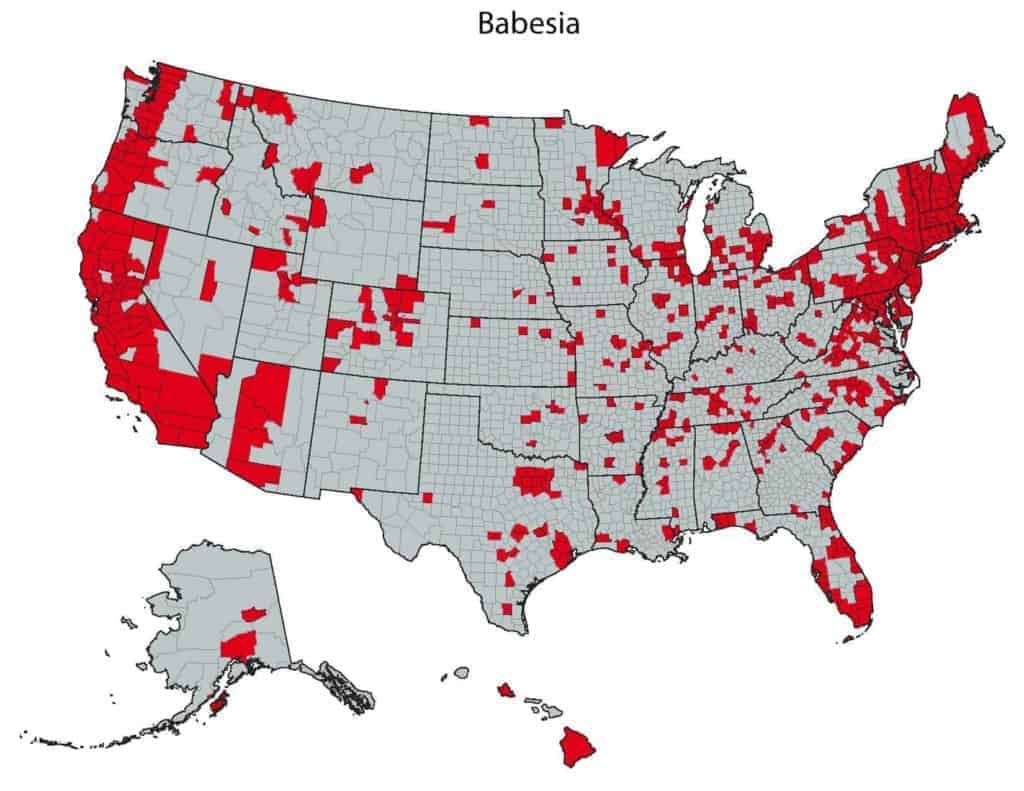

In the United States, Babesiosis is endemic to the same regions as Lyme disease, as it is transmitted by the same ticks: B. microti is spread by the black-legged tick: Ixodes scapularis, the Eastern black-legged deer tick, found on the East Coast and in several mid-western states, and the Western black legged tick, Ixodes pacificus, found on the West Coast. B. duncani is transmitted by D. albipictus, the winter tick. In Europe, on the other hand, the culprit is Ixodes ricinus, also known as the sheep tick or castor bean tick.

Human Babesiosis disease has a worldwide distribution, and in recent years it has been expanding to regions outside its endemic areas. Cases of Babesiosis have been reported both beyond the East Coast and Midwestern United States – such as in Alaska, Hawaii, and in central and Southern states – as well as in countries in Asia, Australia, Africa, and South America. It’s important to note that just because you don’t live in a previously noted endemic area doesn’t mean you can’t get Babesiosis.

If you test negative for one species of Babesia, you may still be infected with another species.

There are over 100 species of Babesia, with several affecting humans. The primary species known to transmit Babesiosis in the U.S. are Babesia microti and Babesia duncani. In addition, Babesia divergens is found in Europe.

Until recently, it was thought that B. microti was found in the Eastern U.S. while B. duncani was prevalent in the Western U.S. However, this is no longer the case, as both species have expanded their range. While B. duncani was once called WA-1 because it originated in Washington state, it’s since been found in California and Oregon, as well as in the Eastern USA. B. microti, on the other hand, has been found all over the U.S., as well as in Switzerland.

Because of these changes in endemicity, it’s crucial that physicians test for both B. microti and B. duncani even if the patient lives outside of those species’ primary regions. If you receive a negative Babesia test for one species, you may still be infected with another species.

Like malaria, Babesia infects red blood cells and causes similar viral-like symptoms.

Babesia not only resembles the malaria parasite, but it also infects the body in the same way: by growing and reproducing inside the red blood cells of the infected person or animal.

While a minority of patients are asymptomatic, many infected people suffer painful, viral-like symptoms due to the rupturing of red blood cells in the body. Unfortunately, like Lyme, Babesiosis disease often presents in nonspecific and intermittent symptoms with varying severity, so it can be hard to detect how sick you are – especially if you don’t remember a tick bite.

Early-stage symptoms of Babesiosis may appear one to six weeks after a tick bite, so keep careful track and talk to your physician about testing for Babesia if you notice viral-like symptoms or other changes to your health.

Common Babesiosis Symptoms

- High fever

- Chills

- Muscle or joint aches

- Fatigue

- Less common symptoms like severe headache, abdominal pain, nausea, skin bruising, yellowing of skin or eyes, and mood changes

- Later-stage symptoms like chest or hip pain, shortness of breath, and drenching sweats

It’s imperative that you remain on alert if you notice any of these symptoms. Untreated Babesiosis, especially for immunocompromised or elderly patients, can lead to complications such as very low blood pressure, liver problems, hemolytic anemia, kidney failure, and heart failure.

Babesiosis disease can be fatal.

The possible complications of Babesiosis disease are severe enough. But for a particular set of immunocompromised patients, the disease can be fatal.

Patients with HIV, cancer, lymphoma, or serious health conditions like liver or kidney disease are especially vulnerable to all of the above complications up to and including death. Babesiosis can also be life-threatening to those who have no spleen (asplenia), as well as elderly patients.

Babesiosis is the most common Lyme disease coinfection.

Patients with Lyme disease often have one or more coinfections or simultaneous infections that can cause additional symptoms or exacerbate one or both diseases’ symptoms. The presence of coinfection can not only make symptoms worse but also complicates the diagnostic and treatment process.

In a study from Lymedisease.org, over 50% of Lyme disease patients from a pool of 3,000 had coinfections. The most common co-infection – at 32% – was Babesiosis disease. If you have a Babesia coinfection, it’s crucial that you get treated for Babesiosis before you can successfully treat your Lyme disease.

However, know that you do not have to have Lyme disease to get Babesiosis.

Prevention, Diagnosis, and Babesia Treatment

How to Prevent Babesiosis Infection

The best way to avoid tick-borne Babesiosis infection is to avoid ticks, always check for ticks after being in tick-endemic areas, know how to remove ticks, and monitor your symptoms carefully if you do get a tick bite. Visit the IGeneX blog for more tips on How to Prevent Lyme Disease and Avoid Tick Bites and What to Do After You’ve Been Bitten By a Tick.

Getting a Diagnosis and Treatment

If you notice any of the above symptoms of Babesiosis disease, it’s important that you get tested at a reputable site with the latest technology in testing for tick-borne diseases. If possible, get tested for multiple species of Babesia – if you come up negative for one species, you still may be infected by a different species.

Your physician should analyze your test results together with your symptoms to come up with an individualized treatment plan for you. Most patients will need to be treated for 7-10 days with a combination of either atovaquone and azithromycin, or clindamycin and quinine. Again, if you have a Babesia coinfection with Lyme disease, it’s crucial that you get Babesia treatment in order to be able to successfully treat the Lyme.

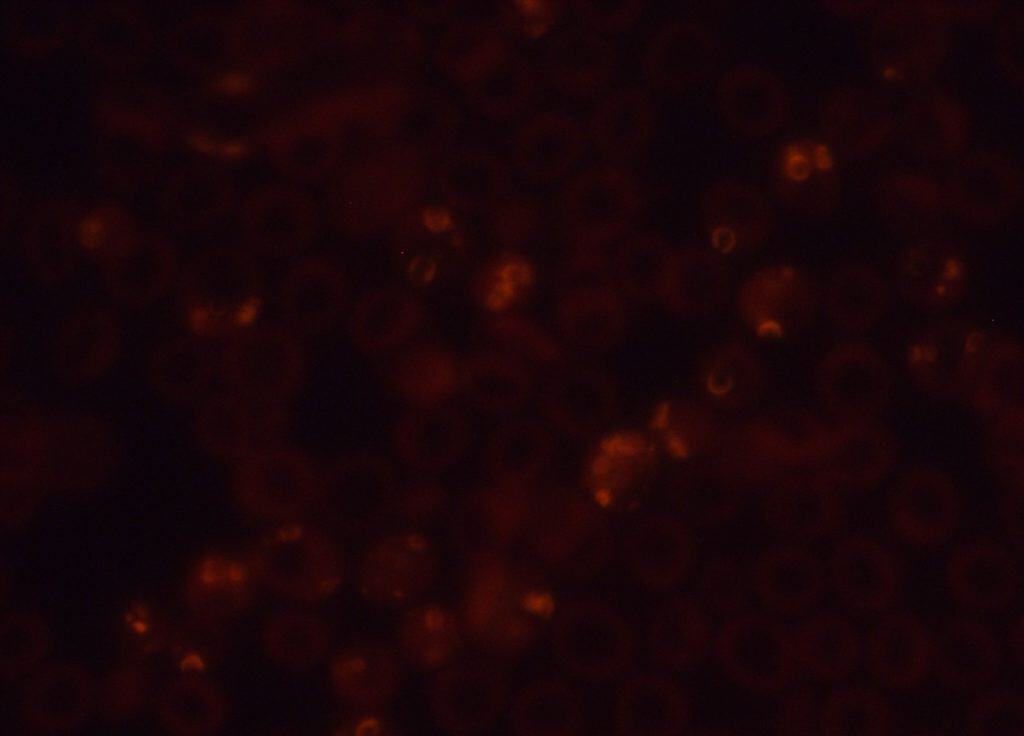

IGeneX offers the most accurate, sensitive, and comprehensive testing for Babesiosis disease. For example, IGeneX is the only lab with a FISH (Fluorescent in-situ hybridization) test for Babesia that detects live parasites by targeting rRNA. Learn how it works today.